|

| Le Corbusier |

Le Corbusier

An influential designer of the early nineteenth century who changed his birth name from Charles-Edouard Jeanneret to Le Corbusier also helped change architecture to what it is known as today. Whether intentional or not, Corbusier and his colleague Ozenfant developed a new movement known as the Purist Movement that formed a segway into the Modern Movement. The academic slides provided in the architecture history course number 327 explains that “Purism championed a traditional classicism with a formal focus on clean geometries, yet it simultaneously embraced new technologies, new materials, and the machine aesthetic.” A parallel thought process to modernism design work.

The 1914 Maison Domino house structure model is a great example of how Corbusier began testing out his design theories and implementing them into full scale instances. This new three-dimensional grid he created allowed the support spans to increase without jeopardizing structural integrity and creating an open, seemingly floating structure. Later in Corbusier’s career he wrote a book titled “First Five Points of Architecture,” it goes on in detail about his main five bullet points of architecture he tends to use in each of his buildings. The foundations for these ideas were laid way back here in the early nineteen hundreds with the Domino House. I would also like to point out his early renditions of the vertical stair tower that ascends from the dark lower portion of the building to the light exposed floors above it, all suspended above the ground on structural elements known as Pilotis.

|

| Maison Domino Structure |

As he journeyed from building to building working and testing his ideas of architecture it is interesting to study the intermediate buildings he developed, like the Ozenfant Residence. Situated within the urban fabric of Paris it holds true to some of his few design principles, but you can see his experiments with the Pilotis, notice how the audience cannot see them, but rather it is one continuous wall façade. He included a glass cube on the corner of the building facing the traffic below where not only the corner where the two walls meet were all glass, but also the roof above. Since the completion of the residence this feature has been changed so that the glass roof is now opaque and supports a garden top outdoor space in the midst of a city. I am not sure who made this final call to change the original plan, but it may be in accordance to Corbusier’s later love for exposed roof gardens and the owner of the Ozenfant Residence was trying to be true to Le Corbusier’s Five Points.

|

| Ozenfant Residence |

|

| Ozenfant Residence Interior |

One of his last structures, Villa Savoy, completed in 1930, may be the best illustration of his Five Points. To reiterate, Corbusier’s First Five Points of Architecture include:

1.) Pilotis: Elevating the mass off the ground

2.) Free Plan: achieved through the separation of the load-bearing columns from the walls subdividing the space

3.) Free Façade: the corollary of the free plan in the vertical plane

4.) Ribbon Windows: long horizontal sliding windows

5.) Roof Garden: restoring, supposedly, the area of ground covered by the house

Villa Savoy is an all white structure located in an open field surrounded by dense forest located outside of Paris. As one approaches the structure they notice three distinct layers to the building: the lower layer dedicated to servant housing, car ports, and the ascension to the upper floors by means of a grand ramp, the main floor where the owner resides looking at the landscape through his ribbon windows, and the ramp completes its journey to the upper roof garden and sun room. A great structure supported by pilotis and elements seen in the Domino house. With this structure having no surrounding context, only vegetation, one questions where the front of the building is. It is left subject to the viewer, possibly a rational is the front is where one enters the building through the lower level car port.

|

| Villa Savoy |

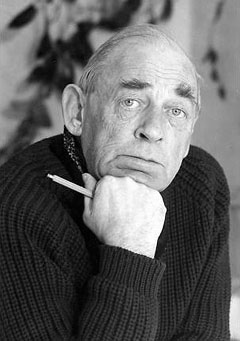

Mies Van der Rohe

|

| Mies van der Rohe |

It is very evident that Mies van der Rohe was a Rationalist to the core. He looked for standardized and repeatable forms that met the needs of the clients that also were considerate of societal needs. He was a German citizen and influenced many individuals and groups of people with his anti-formalistic viewpoints and his early works focusing on Constructivist thinking. Mies was concerned with simplifying problems he faced daily and in design providing him the option to create design solutions in return. Mies had two main design principles that he held to:

1.) The enclosure of function in a generalized cubic container was not committed to any particular set of concrete functions.

2.) The articulations of the buildings in response to the fluidity of Life.

Although Mies and Corbusier’s methodologies were completely different, they’re designs sometimes resulted in similar looking buildings. For instance, the Farnsworth House has raised pilotis and an open plan and contributes a lot to Corbusier’s five points, but it better identifies with Mies’s two points of design stated above. Mies was not focused on tectonic forms and producing buildings in a rugged industrial way, he graphical representation and the craft between the architect and the design to be highly influential.

|

| Brick Country House Plan |

To illustrate that Mies didn’t focus on mechanization, I would like to bring his Brick Country House to mind, developed in 1924. It was a home where in plan it looks like a mouse maze almost. At each intersection the views open up and one is faced with several options to turn with a wide range of visual acuity of the house. It is a journey from one vantage point to the next.

Another structure he designed was the Barcelona Pavilion, arguably one of his most famous. This encompasses a free open plan very well and can be related to his idea of the building responding to the fluidity of life. It combines a tension of opaque planes intersecting with thin airy glass walls, a large water feature, thin columns that seem unable to actually do their job of supporting the ceiling, and presentation planes that are made of rich stone like granite. These planes that act as the only opaque walls in the building act as center pieces. The smoothness and reflectance of the granite walls and floors flow into the water feature outside supporting the fluidity of life.

|

| Barcelona Pavilion |

The Farnsworth House has caused a lot of controversy in the design world and possibly models his two design principles the best. It is an open cube wrapped in glass with few opaque walls. It brings to mind the topic of privacy and how is a family supposed to function in a space open to world to see inside their private home. It also has the idea of fluidity where the main floor of the building steps down to an outdoor receiving platform that then steps down into the landscape. Like Villa Savoy, this is also placed in a natural context. When push comes to shove, the owners are going to want privacy, thus curtains were installed on the glass facades, and how does it deal in the extreme temperatures of winter and summer, these questions beg to ask, is this type of building really suitable for residency?

|

| Farnsworth House |

|

| Alvar Aalto |

Alvar Aalto

Alvar worked in the same era as Mies and Corbusier, but seemed to have a slightly different edge on modernism. His designs were organized around functionality within the space as opposed to Mies whose work didn’t always reflect that, like the Farnsworth residence. In an effort to create his own work he developed new forms and materials that are sensitive to the climate, not too abstract in form, respect its place within the landscape, and gather architectural forms from natural phenomenon. Aalto’s career was a little behind the other two architects, his work mainly inhabited the mid 1900’s.

Aalto’s Experimental House in Finland, completed in 1953 is situated in the middle of a dense forest. It is one with nature with fully designed living quarters as well as an exterior courtyard. Shaped like a “U” it consists of over fifty different brickwork patterns along the wall facades and outdoor courtyard floor. As the floor is the same brick as the walls and there is no kick-plate or anything that visually separates the two, the floor seems to crawl up to the wall. The use of the brick as a main design feature relates back to the Arts and Crafts Movement and the question of craftsmanship.

|

| Experimental House |

Aalto was awarded the commission of designing a residence hall for MIT called the Baker House, which was later built in 1948. With a separation between private and communal areas he decided to separate the two with one long serpentine datum with curvilinear rooms on one side and rectangular open areas on the other. It is interesting that in this modern time that a brick work structure as opposed to steel and concrete was unheard of at the time, adding to the uniqueness of Aalto.

|

| Baker House MIT |

Another work of his that deserves recognition is his Concert Hall that was built in Essen, Germany in 1988. Another way to give account of his separation from the standard modernistic approach is how he metaphorically used function as the main design feature. The wall façade uses repetition and small variances within this repetition to signify a musical score, because after all it is a music hall. Along with the music score repetition he uses black opaque granite to signify piano keys. Overall, a slightly different take on modernism compared to Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe.

|

| Concert Hall Essen, Germany |

Summary

In a sense, it seems all three of the mentioned modernist designers sought to create a list of design principles that included a technique for the organization of buildings to be used specifically as billboards for the new modernistic ideals rather than creating actual structures. Less important to these architects was the actual manifestation of their principles as inhabitable places, because it was through their documented process and teachings, not their commissions, that their influence would become immortal. As their careers progressed they each added to their repertoire of design points. Some were taken out; new ones were added and experimented with only to be thrown out later on until eventually they settled upon their favorites. This is their tested and tried list of design principles they implement in nearly every modern building they design; the ideas that are copied by firms and young architects alike and impacting entire cities that can still be seen today, nearly five to seven decades later.